Original Written by: Deve Persad on February 27, 2014

For almost three years we have been a one car (notice that it starts with “C”) family. This past year my son obtained his driver’s license. As a result we needed to purchase another vehicle. We did so, gladly, even willingly. Research was done, test drives were done, we even waited for a sale and then, a brand new vehicle was purchased and taken home to it’s own spot in our garage. He is now the proud owner of a new twenty-one speed bicycle. We still have the one car, but now he joins his mother and I as having an extra set of wheels with which to get around town.

Culture (another “C” word)

We often talk about what culture is. We can do that with a tremendous amount of expertise, mostly because we are part of it. It seems easy to see and simplistic to figure out: Culture is the ordered way of the life we live in the place we live it, with the people we live among. What we don’t often talk about is how culture is shaped. Nor do we talk about what culture isn’t. In, The Rebel Sell: Why The Culture Can’t Be Jammed, Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter, take us on a socieo-economic adventure through our understanding of culture, counterculture, consumerism while accenting the current consequences (notice the C’s) in which we, despite our continued efforts, now live. (Loc. 151)

What if there’s more to culture than that? “Culture is built upon the subjugation of human instincts. The progress of civilization, therefore, is achieved through a steady increase in the repression of our fundamental instinctual nature and a corresponding decrease in our ability to experience happiness. ”(Loc. 569). This is a significant part of what Heath and Potter desire us to learn. We consider culture what we’re part of without giving thought that we build a culture by excluding ourselves from other influences. The choices we make both for and against contribute to the culture in which we live. And the irony is, while we strive to live, achieve and become masters of our culture, our capacity for contentment diminishes because in the end we are never truly satisfied with what our culture offers to us. We seem to have a running list of pieces from other cultures we would never want as well as another list from cultures in which we aspire to belong.

Counterculture (“C”)

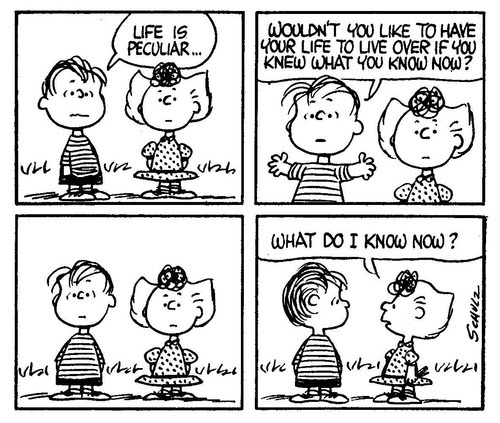

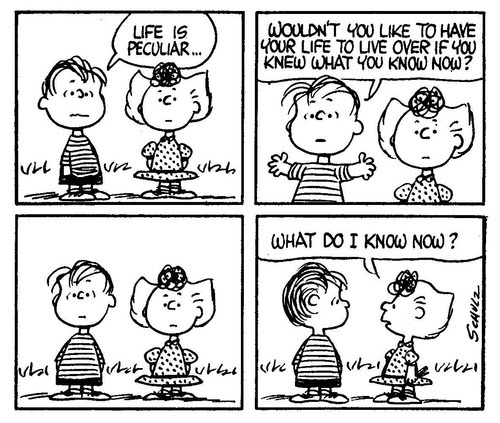

So we rebel. We look for a different way than the ‘norm’, not realizing that we can only differentiate from the norm that we see. Our rebellion while at first refreshing places us within a new “normal” that is already populated by those who will before long be looking for their new “normal”. They may even switch to our old “normal”, but it will be new to them. That’s the confusion called the countercultural rebellion in which we currently find ourselves cornered. (Loc. 2049)

Consumerism (“C” again…)

Consumerism is not a disease, it is a symptom of a deeper problem. We tell ourselves that we’re searching for our identity within the culture, yet we continue to be captivated by the appeal of advertising, which channels the flow of our income (and credit) into a quest that is not individuality but rather achieves a social status. Advertising is not to blame, the selfish greed that goes unchecked is what provides the advertising fuel. (Loc. 3314)

“When people complain about a threat to their individuality or to their identity, what they are really reacting to is a threat to their status, imposed by the competitive structure of hip consumerism…But what we are all really after is not individuality, it is distinction, and distinction is achieved not by being different, but by being different in a way that makes us recognizable as members of an exclusive club. This makes our choices eminently predictable…” (Loc. 3380-3385)

Consequences (I think you’ve got it by now)

As the cultures through which we strive to make our upward climb in social status ebbs back and forth because of the countercultural movements that are now inherent, the swill becomes a mesmerizing blur. Add into that idea the increased multi-cultural, ethnic influences and the homogenous foundation of our capitalistic economies, there is no doubt that confusion abounds (Loc. 3875).

But what if the conclusions for our cultural confusion can’t be crafted from a “C” word?

“The kingdom of heaven is like a treasure, hidden in a field, that a person found and hid. Then because of joy he went and sold all that he had and bought that field.” – Matthew 13:44

It’s a one line parable, whose truth is sometimes hard to grasp and I certainly don’t pretend to have uncovered the depth or breadth of its application. But I often wonder if the person in this story had to tell others about why he would sell off what he possessed, to purchase a field that wasn’t wanted by another or desired by other purchasers. I wonder how they went about re-establishing themselves in society. I wonder about how vulnerable they made themselves to being dependent upon others. I wonder about the ridicule that came as a result of the status they seemed to have given up, yet unseen was the exchange they were making for a different set of values, a different order to their lives, a different purpose. There is something captivating about the now and not yet of the Kingdom of Heaven, that causes us to abandon cultural principles in exchange for the transcendence of supra-cultural (it starts with an “S”) principles . We are not without rules, guidelines or protocol or habits, but they interact in different ways with the rapidly changing dimensions of our omnicultural (to use Heath & Potter’s word) society. By them we can enjoy a unique freedom of almost random movement from within society because of our motivations of the Kingdom culture that is not yet.

Our choice, at this point, to stay as a one car family, has freed significant cash flow that we now use to support and participate in local and global areas of need. We have not perfected the supra-cultural approach to which we aspire. We still have our own indulgences that can effectively be questioned. And, while we live in relative simplicity from some of our peers, we realize that we also live in extravagance from others. But…

What if the identity that we are constantly pursuing cannot be discovered by the consumption of goods, the clothing we wear or the status we fight to achieve? What if our identity never comes from within culture? What if our identity could allow us to be at home in many cultures, transcending all cultures? What if our identity is supra-cultural?

To C or not to C that is a good question?

For almost three years we have been a one car (notice that it starts with “C”) family. This past year my son obtained his driver’s license. As a result we needed to purchase another vehicle. We did so, gladly, even willingly. Research was done, test drives were done, we even waited for a sale and then, a brand new vehicle was purchased and taken home to it’s own spot in our garage. He is now the proud owner of a new twenty-one speed bicycle. We still have the one car, but now he joins his mother and I as having an extra set of wheels with which to get around town.

Culture (another “C” word)

We often talk about what culture is. We can do that with a tremendous amount of expertise, mostly because we are part of it. It seems easy to see and simplistic to figure out: Culture is the ordered way of the life we live in the place we live it, with the people we live among. What we don’t often talk about is how culture is shaped. Nor do we talk about what culture isn’t. In, The Rebel Sell: Why The Culture Can’t Be Jammed, Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter, take us on a socieo-economic adventure through our understanding of culture, counterculture, consumerism while accenting the current consequences (notice the C’s) in which we, despite our continued efforts, now live. (Loc. 151)

What if there’s more to culture than that? “Culture is built upon the subjugation of human instincts. The progress of civilization, therefore, is achieved through a steady increase in the repression of our fundamental instinctual nature and a corresponding decrease in our ability to experience happiness. ”(Loc. 569). This is a significant part of what Heath and Potter desire us to learn. We consider culture what we’re part of without giving thought that we build a culture by excluding ourselves from other influences. The choices we make both for and against contribute to the culture in which we live. And the irony is, while we strive to live, achieve and become masters of our culture, our capacity for contentment diminishes because in the end we are never truly satisfied with what our culture offers to us. We seem to have a running list of pieces from other cultures we would never want as well as another list from cultures in which we aspire to belong.

Counterculture (“C”)

So we rebel. We look for a different way than the ‘norm’, not realizing that we can only differentiate from the norm that we see. Our rebellion while at first refreshing places us within a new “normal” that is already populated by those who will before long be looking for their new “normal”. They may even switch to our old “normal”, but it will be new to them. That’s the confusion called the countercultural rebellion in which we currently find ourselves cornered. (Loc. 2049)

Consumerism (“C” again…)

Consumerism is not a disease, it is a symptom of a deeper problem. We tell ourselves that we’re searching for our identity within the culture, yet we continue to be captivated by the appeal of advertising, which channels the flow of our income (and credit) into a quest that is not individuality but rather achieves a social status. Advertising is not to blame, the selfish greed that goes unchecked is what provides the advertising fuel. (Loc. 3314)

“When people complain about a threat to their individuality or to their identity, what they are really reacting to is a threat to their status, imposed by the competitive structure of hip consumerism…But what we are all really after is not individuality, it is distinction, and distinction is achieved not by being different, but by being different in a way that makes us recognizable as members of an exclusive club. This makes our choices eminently predictable…” (Loc. 3380-3385)

Consequences (I think you’ve got it by now)

As the cultures through which we strive to make our upward climb in social status ebbs back and forth because of the countercultural movements that are now inherent, the swill becomes a mesmerizing blur. Add into that idea the increased multi-cultural, ethnic influences and the homogenous foundation of our capitalistic economies, there is no doubt that confusion abounds (Loc. 3875).

But what if the conclusions for our cultural confusion can’t be crafted from a “C” word?

“The kingdom of heaven is like a treasure, hidden in a field, that a person found and hid. Then because of joy he went and sold all that he had and bought that field.” – Matthew 13:44

It’s a one line parable, whose truth is sometimes hard to grasp and I certainly don’t pretend to have uncovered the depth or breadth of its application. But I often wonder if the person in this story had to tell others about why he would sell off what he possessed, to purchase a field that wasn’t wanted by another or desired by other purchasers. I wonder how they went about re-establishing themselves in society. I wonder about how vulnerable they made themselves to being dependent upon others. I wonder about the ridicule that came as a result of the status they seemed to have given up, yet unseen was the exchange they were making for a different set of values, a different order to their lives, a different purpose. There is something captivating about the now and not yet of the Kingdom of Heaven, that causes us to abandon cultural principles in exchange for the transcendence of supra-cultural (it starts with an “S”) principles . We are not without rules, guidelines or protocol or habits, but they interact in different ways with the rapidly changing dimensions of our omnicultural (to use Heath & Potter’s word) society. By them we can enjoy a unique freedom of almost random movement from within society because of our motivations of the Kingdom culture that is not yet.

Our choice, at this point, to stay as a one car family, has freed significant cash flow that we now use to support and participate in local and global areas of need. We have not perfected the supra-cultural approach to which we aspire. We still have our own indulgences that can effectively be questioned. And, while we live in relative simplicity from some of our peers, we realize that we also live in extravagance from others. But…

What if the identity that we are constantly pursuing cannot be discovered by the consumption of goods, the clothing we wear or the status we fight to achieve? What if our identity never comes from within culture? What if our identity could allow us to be at home in many cultures, transcending all cultures? What if our identity is supra-cultural?

To C or not to C that is a good question?

Comments

Post a Comment